Leo Yeni

- Art

An Artist’s Paper Life

View details about the event: Leo Yeni

Civilian Internment in Fascist Italy

Co-presented with Centro Primo Levi

On the occasion of the English language publication of

Mussolini’s Camps

Civilian Internment in Fascist Italy (1940-1943)

(2019, Routledge)

[I campi del duce,Turin: Einaudi, 2004]

Panelists:

Silvana Patriarca, Fordham University

Carlo Spartaco Capogreco, Università della Calabria

Rudolf Mrazek, University of Michigan

Discussant:

Mary Gibson, CUNY Graduate Center | John Jay College of Criminal Justice

Capogreco’s book focuses on the Italian concentration camps between 1940 and 1943 and contextualizes them in the history of civilian detention between the rise of colonialism and the totalitarian era. When originally published in the popular Einaudi series of Gli Struzzi, Mussolini’s Camps made a statement, both historiographical and political, on the lack of public focus on the history of state violence and the parallel crystallization of the memory of Auschwitz to stand for every form of abuse perpetrated in the Nazi-Fascist era.

Sixteen years after it first came out, one of the underlying questions of the book has acquired relevance beyond the borders of Italy. While there is no doubt about the extreme violence Auschwitz represents, can it represent thousands of concentration camps? And what are the consequences of making such high standard of evil a measure of civility? What were those concentration camps (the majority) where no killing was explicitly planned but where anything would have been allowed to happen within a state of exception justified by public order and national security?

When, in 2004, after 20 years of research, Mussolini’s Camps appeared in bookstores, hardly anything was known about fascist civilian internment and about the concentration

camps and confinement locations established by the fascist regime following Italy’s entry into the war. Target of this operation were “foreigners of enemy states, Slovenians and

Croats with Italian citizenship, politically dangerous subjects, and Jews who, as refugees or for other reasons, had come to Italy from countries that practiced racial policies,” therefore not enemy states.

The sites of the Italian camps had been forgotten and, in most cases, their physical places carried no plaque or sign of their past. It was largely thanks to Carlo Spartaco Capogreco, at that time a researcher by passion turned academic historian, that they were eventually identified, publicly acknowledged, and became the object of broader study.

His extensive research sparked interest and praise in the academic world and contributed to open an important phase of re-evaluation of the apologetic image Italy had built for itself after the war. Politicians and pundits did not wait to react: how could these “benevolent” camps where so many Jews ultimately survived, be called “concentration camps” and thus compared to the Nazi death camps?

Capogreco’s work offers solid primary sources and historiographical tools to deconstruct these questions as well as the assumptions that prompted and continue to feed them.

He documents in detail the juridical and executive frame in which the arrests and internment occurred; the logistics of the camps; the varying degree of abuse and violence; the lack of food; the mutating language used to publicize or conceal detention; the inexplicable bureaucratic labyrinth that added psychological burden to the physical isolation; the often ambiguous nature of humanitarian intervention, the separation of families. Not last, the author traces the monetary component of internment involving both the circulation of large amounts of public money and various forms of exploitation of the internees.

Among the innovations of the book, is the attempt to consider on the same map the broad repressive effort that Italians enacted both on domestic territory and in Yugoslavia where over 5,000 people, many of them children and adolescents, were amassed in the camp of Rab and decimated in great numbers by hunger and illness.

The section dedicated to Jewish internment depicts the condition of limbo and legal void in which thousands of Jews lived in the Italian camps until the progress of the war determined their liberation (for the camps in the South where the Anglo-American forces arrived in the summer of 1943) or their flight and in many cases deportation to Auschwitz (from the camps that remained under Mussolini’s rule and the German allies).

Mussolini’s Camps opens a window onto the experience of the internees and that of the police, clergy, and lay personnel who implemented internment or became part of its management.

The questions arising from Capogreco’s investigation do not concern the ultimate horror, hatred and a view of evil that can be safely separated from post-war values. Instead, they address a grey area recognizable in modern-day societies: the abandonment of groups of human beings to the unexpected, the unplanned, to an area lying outside of any social or political horizon. Not hatred but lingering prejudice ready to be harnessed in the name of a certain conception of justice. Not evil schemes but men and women who feel compelled to “protect” the nation, family and religion. Capogreco portrays the intersections between the world of the free and that of the detainees—the fact that they were able to pray, celebrate, play music or teach— not as a symbol of heroic resilience or authoritarian benevolence, but as part of a reassuring farce whose end was left open to any outcome convenient for those in power.

By the time Mussolini opened his 1940 concentration camps, the idea of forced “concentration” of civilians had already a long history. As Capogreco shows, Italy had itself used it in Libya and East Africa, while perfecting a large detention and confinement system against political dissenters. The Germans had established concentration camps during the Herrero genocide in their South-African colonies and the Spanish and British used civilian concentration in Cuba and South Africa. During the Armenian genocide, the Turks segregated hundreds of thousands of people and then drove them to the desert where they were ultimately starved to death. Both the Tzars and the Soviets had used deportation and confinement to Siberia as means of repression. In the US, the Indian Removal Act of 1830 imposed one definition onto all native people to forcibly “relocate” them in delimited areas.

Italian resistance to acknowledging its own concentration history is not isolated and reflects the need for narratives and language capable of concealing continuity between colonial enterprises and domestic democracy, the totalitarian era and the post-war. With due differences, the Italian case resonates with the current conflicts in the US over the use of the term “concentration camp” and may provide useful tools to examine its dynamics. In both cases, the confrontation occurs between attempts to imagine and analyze historical process and claims to static and unchallengeable truths.

Fascism and Nazism refined their means of repression within the liberal system and over the course of time. They used the rule of law to shape various forms of moral and ultimately physical segregation. Death camps, Auschwitz in particular, have become a symbol of the tragedy that lays at the end of this process. In the collective perception however, the process has retained little or no importance. The evolution from the segregation of a group to its eventual elimination is increasingly absent from popular narratives.

The product of a totalitarian project which, from 1943 on, was completely integrated in the system of extermination of the Jews, Mussolini’s camps have been read as a “lesser evil” or even as a “lesser good”. Allegedly this interpretation is based on their distance from Auschwitz. By separating their historical analysis from the post-war judgement, Capogreco proposes the possibility to place emphasis not on the distance from Auschwitz but on the proximity to the post-war society, one still shaped by ideas of national superiority, this time based not on imperial dreams and muscular strength, but on the narrative of Italian empathy and tolerance. The point of contention was not so much the history of the persecuted but the perception of self that Italians could derive from a particular reading of history.

In 1946, George Orwell observed that political language seeks wordings that can stand in “defence of the indefensible”. His observation may be helpful to consider the conflicts over the language of concentration camps both in Italy and in the US.

The question of language clearly predates the post-war era. Fascism devoted a great deal of attention to calibrating its political vocabulary. The consequences were far-reaching. For instance, prisoners were organized in a hierarchy spanning from “subjects endangering national security” to “free internees”. This euphemism for a form of remote confinement that ultimately lead to many deportations, had a confounding effect on both the victims and the public that witnessed the detention of families, women, elderly and children. Apologists still herald the term today to exemplify Italian benevolence and contend, against historical evidence, that internment was not a deprivation of freedom nor did it endanger those who were subjected to it.

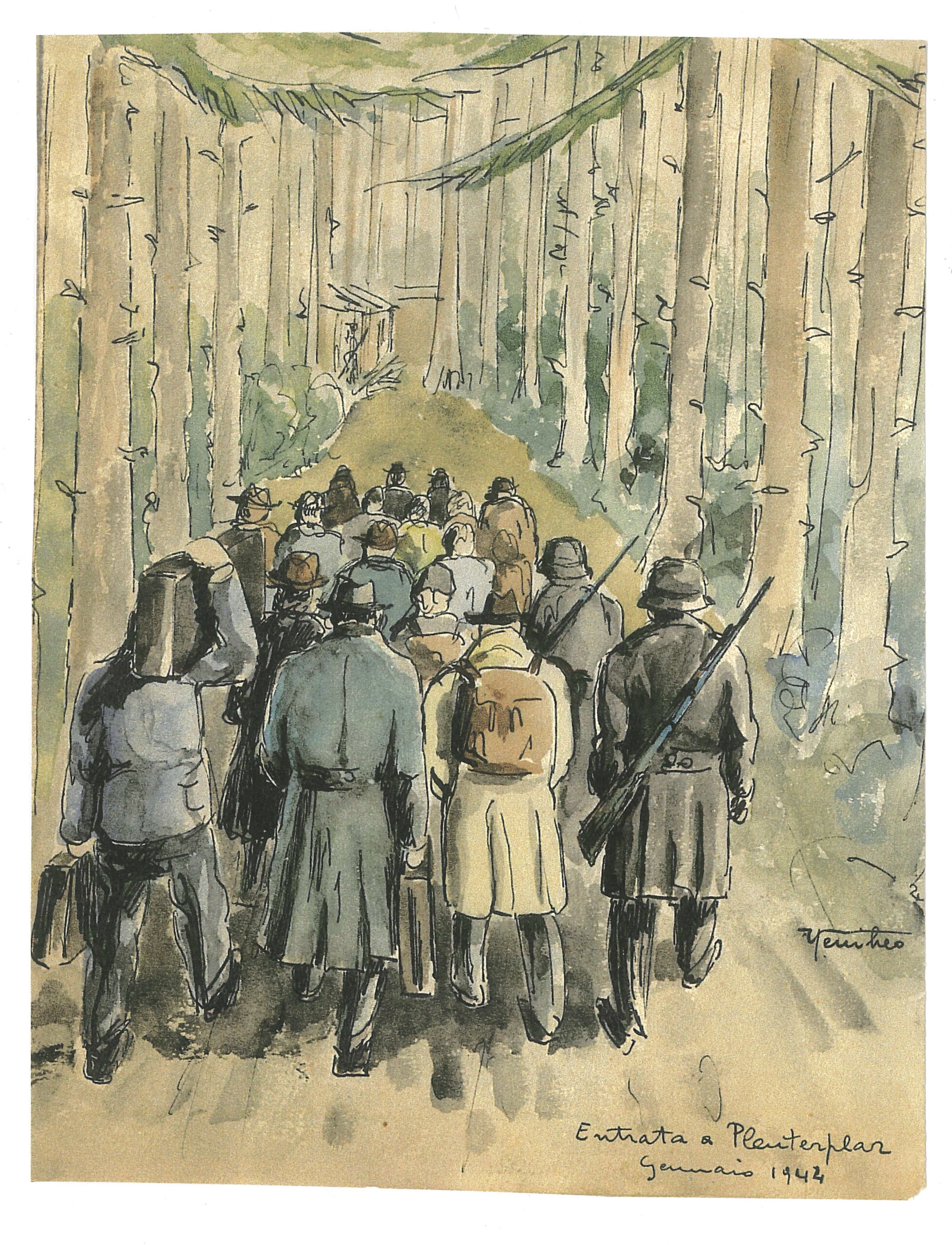

As Capogreco’s research unveils, the persecuted too were confronted with questions of language and sensed that their survival depended on the possibility to understand what a name meant: in 1940, while being transferred from prison to a concentration camp, the 26 year old Maria Eisenstein, a Viennese literature student in Italy, pondered in her diary “What exactly is a concentration camp? We completely lack data and try to find a common denominator between the Isle of Man and Dachau …”.

In ENGLISH.