Studi sullo stile di Bach

Luigi Attademo (guitar) with Laura Croce (narrator)

View details about the event: Studi sullo stile di BachThis site uses cookies. If that’s okay with you, keep on browsing, or learn more about our Privacy Policy.

Luigi Attademo (guitar) with Laura Croce (narrator)

View Details View details about the event: Studi sullo stile di Bach

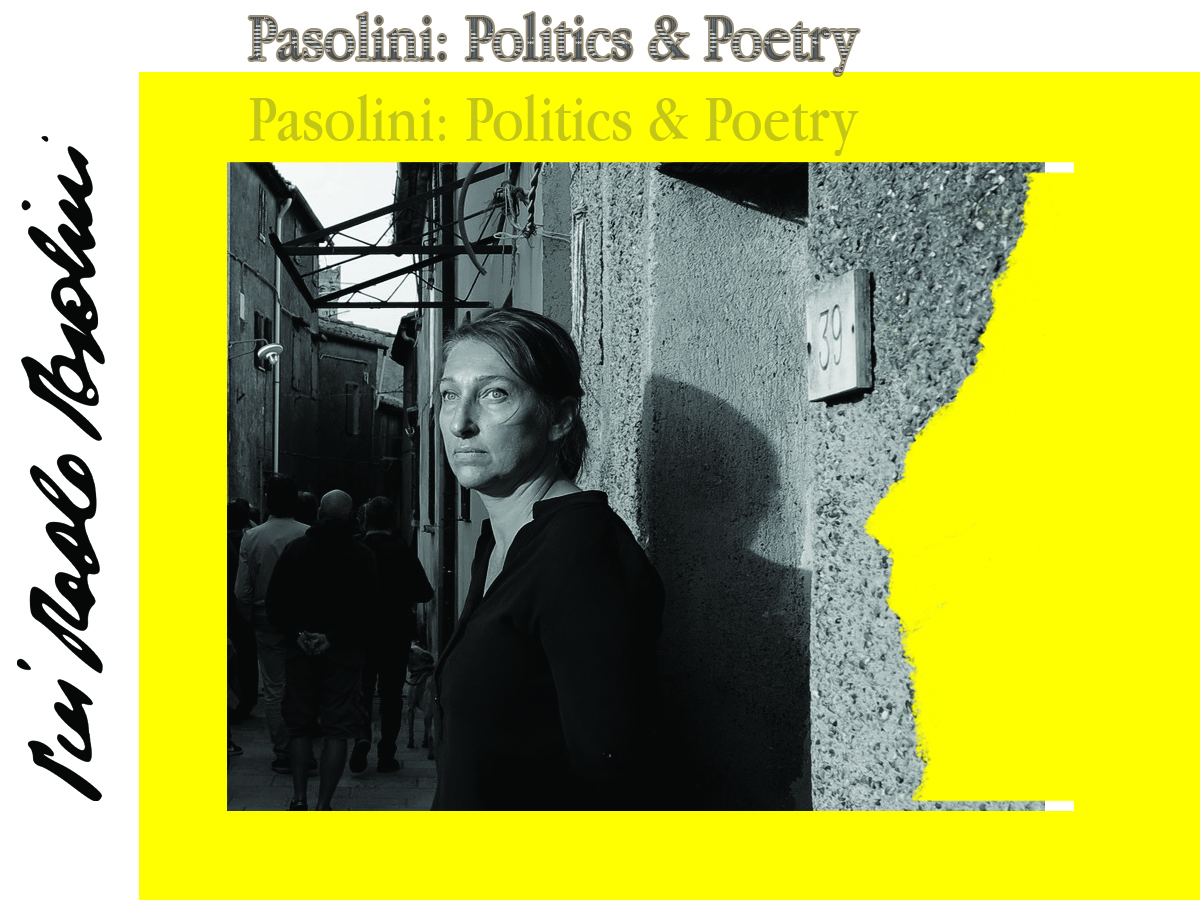

“What Makes It Italian?” Famous Composers and the Italians Who Taught Them

View Details View details about the event: What Busoni Taught Kurt Weill

at NYU Deutsches Haus (42 Washington Mews)

View Details View details about the event: TERRA, Earth Meets Piano

Introduced by Ara H. Merjian (NYU)

View Details View details about the event: La ricotta | La rabbia

Casa Italiana Zerilli-Marimò at New York University was founded in 1990 by Baroness Mariuccia Zerilli-Marimò with the goal of promoting Italian culture by offering a program of free events, open to everyone, on all topics related to Italian studies, including language, literature, cinema, music, theater, visual art, as well as politics, economics, and lifestyle.

In 1988, Baroness Zerilli-Marimò’s donation enabled the purchase and meticulous restoration of our 19th-century historical landmark building. NYU’s President Dr. Brademas, during the project announcement, commended her vision for fostering cultural ties with Italy’s rich heritage. Baroness Zerilli-Marimò, driven by intellectual curiosity, intended this venture as a permanent homage to her husband, Guido Zerilli-Marimò, and a means of enhancing knowledge of Italian culture in the United States.

Inaugurated in 1990, Casa Italiana consistently surpassed expectations. It provided a prestigious home, that allowed the foundation and growth of the Department of Italian Studies, now one of the largest and most prestigious in North America. Casa Italiana began offering a diverse array of public cultural events under Director James Ziskin. Professor Stefano Albertini, taking over in 1998, transformed it into a prominent center for cultural discourse in New York City, contributing to establishing NYU’s status as a global leader in European and international studies.

Lectures, conferences, performances, screenings, exhibits, and video productions occupy a prominent position in its programming.

Casa Italiana, situated in a 19th-century brownstone, was built between 1851-1852 by Charles Partridge, displaying an Anglo-Italianate style with ornate cornices and decorative doors and windows.

An elegant marble atrium, flanked by original columns, leads to a serene garden with a fountain in the rear.

Located in Greenwich Village, a historic immigrant hub, the brownstone’s construction likely benefited from skilled Italian artisans drawn to the area.

Originally the residence of General Winfield Scott, who served his country for five decades, the building took on significance when Scott moved the Army headquarters to New York in 1852 after losing the presidential elections. He resided there with his wife for eight years. In 1861, Scott thwarted an assassination plot against President Abraham Lincoln and was commended for his service before retiring at age 75.

In 1974, the Winfield Scott House gained historical monument status and was added to the national registry of monuments.

Meet the Casa Italiana Zerilli-Marimò team, a group of people seamlessly blending their passion for Italy and its culture with an insider’s understanding of American society. Beyond their official roles, team members actively contribute to collaborative decision-making, infusing their work with enthusiasm and expertise. Each member has played a crucial role in proposing and curating successful programs and events, shaping Casa into the dynamic cultural center it is today.

This collaborative spirit extends to around a dozen NYU students from diverse backgrounds each year, both graduate and undergraduate. They actively contribute to Casa’s initiatives, gaining valuable skills that propel them toward successful futures. The synergy between experienced team members and the fresh perspectives of student collaborators creates a dynamic environment that reflects the ever-evolving dialogue of Italian and American cultures.

Director

Media and Communications Specialist

Administrator

Program Coordinator

The Advisory Board of New York University’s Casa Italiana Zerilli-Marimò supports the cultural activities of the Casa by the identification of cultural interests, the development of strategies for contact with the American and Italian cultural scene, and suggestions regarding financial support.

The members of the Board are prominent Italian and American personalities in the fields of culture, art, finance, and public service. Baroness Zerilli-Marimò was the Chairwoman of the Board from its inception until her death in 2015. Giorgio Spanu was elected Chairman on April 15, 2016.

Chairman

Giorgio Spanu was born in Iglesias, Italy and currently lives in New York. After completing his studies at the University of Pisa in 1978, he moved to Paris where he held positions in marketing, software publishing & distribution. He was also the co-founder of IVAO, a company specializing in video images managed by computers. Since 1989, with his wife Nancy Olnick, he is the co-founder of the Olnick Spanu Collection focusing on Modern and Contemporary Italian Art, Murano glass, Ceramics, Design, and Art books. The activities of the Collection include the Olnick Spanu Art Program (OSAP), an annual art residency program for Italian artists in Garrison, NY, as well as the publication of books and production of films dedicated to contemporary Italian art, design, and architecture. He is a benefactor of several institutions including: Manitoga/The Russel Wright Design Center, Boscobel, Putnam History Museum, Garrison Institute, DIA Art Foundation, Scenic Hudson, LongHouse Reserve, National Audubon Society, The Museum of Arts and Design (MAD), The Vignelli Center for Design Studies at Rochester Institute of Technology.

Legacy Member

Maria Chiara Zerilli is the daughter of Baroness Zerilli-Marimò, and currently resides in Switzerland.

Legacy Member

Tao Kulczycki is an Italian artist currently based in New York. He obtained his MFA in Sculpture from Pratt Institute, Brooklyn (NY) in 2013 and his BFA in Arts, Performance and Digital Media from Kingston University (UK) in 2010. Kulczycki’s work can be summarized as a hybrid between the self, the surreal and the symbol reflecting present day life and our state of mind. His work involves modifying objects and their concepts. He is the grand-son of Baroness Zerilli-Marimò.

Linda G. Mills became the 17th president of New York University on July 1, 2023. President Mills is also the Lisa Ellen Goldberg Professor of Social Work, Public Policy, and Law and founder of the NYU Center on Violence and Recovery. Mills is a fellow of the American Academy of Social Work and Social Welfare, the country’s leading honorific society of scholars dedicated to excellence in the field.

Prof. Antonio Merlo is Anne and Joel Ehrenkranz Dean of the Faculty of Arts and Science. Born in Italy in 1963, he received a Laurea summa cum laude in economics and social sciences from Bocconi University in Milan in 1987.

Merlo emigrated to the United States in 1988 and earned a PhD in economics from New York University in 1992. Between 1998 and 2000 he held a joint appointment in the Department of Economics and the Department of Politics at New York University.

In 2000, he joined the faculty at the University of Pennsylvania, where he held the Lawrence R. Klein Chair of Economics and the Directorship of the Penn Institute for Economic Research (PIER) until 2014. He was also the chair of the economics department from 2009 to 2012. In 2014, Merlo joined Rice University as the George A. Peterkin Professor of Economics, the chair of the economics department, and the Founding Director of the Rice Initiative for the Study of Economics (RISE). From 2016 to 2019, he served as dean of the Rice University School of Social Sciences.

Eugenio Refini is the Department Chair and a Professor of Italian at NYU. He holds degrees from the University of Pisa and the Scuola Normale Superiore of Pisa. Refini’s research focuses on reception, translation, and adaptation, spanning rhetoric, poetics, drama, music, and voice studies. Notable publications include “Per via d’annotationi” (2009), “The Vernacular Aristotle” (2020), “Staging the Soul: Allegorical Drama as Spiritual Practice in Baroque Italy” (Legenda, 2023). He previously taught at Johns Hopkins University and has received prestigious fellowships, including the NEH Rome Prize.

Ambassador Maurizio Massari is a career diplomat with over thirty years of experience. He has also served as the Permanent Representative of Italy to the European Union (June 2016 – May 2021), and as Special Envoy of the Italian Foreign Minister for the Mediterranean and the Middle East (2012-2013).

He holds a Master’s Degree in International Public Policy from Johns Hopkins University, a Fellowship’s Certificate from the Weatherhead Center for International Affairs of Harvard University, and a Degree in Political Science from the Istituto Universitario Orientale in Naples.

Ambassador Mariangela Zappia is a career diplomat with over thirty-five years of experience, and the first woman in her country to hold this position, as she was the first woman Permanent Representative of Italy to the United Nations in New York and to the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO).

She has also been the first woman Diplomatic Advisor to the Italian Prime Minister and G7/G20 Sherpa. She holds a Master degree in Political Science and International Relations from the University of Florence and a Post-graduate degree in Diplomatic and International Relations from the same University. She has followed periodic high-level training courses on diplomatic practice and management at the Diplomatic Academy of the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Rome.

Fabrizio Di Michele was appointed as Consul General of Italy in New York, covering the State of New York, the State of Connecticut and Bermuda in 2021. An Italian diplomat with 26 years of experience in the field of international relations, he was born in Palermo, graduated in Political Science from the University of Florence in 1992, and joined the Italian Foreign Service in 1995. From 1997 to 2000 he served at the Embassy of Italy in Kinshasa, (DRC), and from 2000 to 2004 he was posted at the Italian Embassy in Beijing (PRC).

Between 2004 and 2007 he served at the Cabinet of the Foreign Minister, working with the succeeding Ministers in office. From 2007 to 2011 he was posted at the Permanent Mission of Italy at the European Union, dealing with EU relations with the Balkans and the Middle East. From 2011 to 2015, he worked as Chair of the Maghreb-Mashreq Working Group of the European External Action Service in Brussels.

Upon returning to Rome, he served in the General Directorate for Political and Security Affairs of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs as the Italian Envoy for the International Coalition against ISIL and Syria – from 2015 to 2018 – and then as Head of the Directorate for the Russian Federation, Eastern Europe, the Caucasus and Central Asia – from 2018 to March 2021.

Comm. Stefano Acunto is a business and non profit leader as Chairman, Trustee and Director of a number of institutions.

Mr. Acunto is Chairman of Beacon International Holdings, into which he consolidated his several businesses in 2018. Today, Beacon is among the leading financial publishing companies in the world in the risk and insurance fields, with more than 150 journalists and media staff in Chicago, New York, London, Milano, Ammann, Mumbai and Singapore (see www.big.com). .He is President of NYREX Development Corp, managers of the New York Insurance Exchange.

He is a Director of Maya Insurance and Credit Global.

Mr Acunto is Trustee, John Cabot University of Rome and Trustee Emeritis of the University of Mt St Vincent.

Mr. Acunto served from 2002 to 2017 as Hon. Vice Consul for Italy in New York State.

Chairman and principal sponsor of the Italian Academy Foundation, Inc (IAF) founded in 1947, IAF’s “cultural diplomacy” initiatives have included more than 60 concerts in New York and Italy, as well as fine art shows, films and publications. . For his work on behalf of Italy in the United States, he was decorated with the rank of Commendatore, Order of Merit, Republic of Italy, and, in 2010, received Italy’s Star of Solidarity, Grande Ufficiale (Stella della Solidarietà).

He holds his B.A. and M.A. degrees (1971, 1973) in classical philology from New York University. He was graduated from Mt St Michael Academy.

He enjoys recounting the fact that, during his years of study at NYU, before Casa Italiana and the Baronessa Zerilli Marimo’s initiatve, Italian studies were housed marginally within the French department’s small quarters.

He and his wife, Carole Haarmann Acunto, divide their time among residences in Greenwich, Connecticut, Rome and Palm Beach. Their daughter, Claudia Palmira, resides in Rome, Italy, with her husband, Mauro Benedetti and their son, Ludovico. The Acuntos’ son, Stephen, his wife, Dr. Veronica White, and their sons, Enrico and Edoardo, reside in Princeton, NJ.

Giovanni Bazoli is an Italian banker. He is chairman of the supervisory board of Italian bank Intesa Sanpaolo and chairman of financial company, Mittel. He was professor of Administrative Law and Public Law at the Università Cattolica in Milan until retiring from his university career in 2001.

Valentina Castellani is an art dealer based in New York. She was born in Boston and raised in Turin. She graduated in Greek Archaeology and Art History and moved to London, where she began her career as a trainee at Sotheby’s. She worked for many years as artistic director at the Gagosian gallery in New York.

Isabella del Frate was born in Rome, Italy and currently resides in New York, where she is an art advisor promoting Italian and European art in the US. She also serves as president of the Murray & Isabella Rayburn Foundation, Trustee of the Strang Cancer Prevention Center, and member of the boards of the Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Save Venice, Inc., and Teatro alla Scala Foundation, USA.

Patrizia di Carrobio is the author of two Italian style classics: Diamanti: Una Guida Personale (Diamonds: A Personal Guide) and Conoscere i Gioielli: Come Sceglierli e Portarli (Knowing Jewels: How to Choose and Wear Them). An international dealer of precious gems and vintage jewelry for more than 30 years, she began her career at Christie’s in New York in 1980, quickly becoming one of the firm’s senior gem appraisers, and eventually heading the Jewelry Department. She serves on the boards of the Philharmonic Orchestra of the Americas and the Limon Dance Organization. She also volunteers for Bottomless Closet, a non-profit group that provides training and professional attire to disadvantaged women for job interviews.

Marilena Citelli Francese holds a degree in archaeology and ancient literature and a diploma in interior architecture at the Camondo Museum in Paris. She has always been interested in the Italian artistic heritage and international relations and has organized many important events, exhibits and celebrations relating to Italian culture in different countries.

Katherine LaGuardia, M.D. is an Obstetrician/Gynecologist and Public Health physician with over 25 years of experience in the field of reproductive care and research, technology innovation, and non-profit program development. She is Chair of the Fiorello LaGuardia Foundation, and previously worked with the Rockefeller Foundation. Dr. LaGuardia formerly was Director of Women’s Health at Cornell from 1989-96 and Director of Clinical Affairs at Ortho McNeil Pharmaceuticals from 2001-10. In 2014, Dr. LaGuardia joined the de Blasio administration as a Special Advisor at the Dept. of Health & Mental Hygiene.

Frank J. Guarini represented New Jersey’s 14th Congressional District in the US House of Representatives for 7 terms beginning in 1978. He received his BA from Dartmouth and his JD and LLM degrees from New York University School of Law. He later pursued advanced studies at The Hague Academy of International Law in the Netherlands.

In Congress, Mr. Guarini was a member of the Ways and Means and served on Taxation and Trade Committees and was involved in important initiatives including Free Trade Agreements with Canada, Israel, and Mexico, and Tokyo. He served on the Budget Committee and the chairman of the Task Force for Urgent Fiscal Issues. Currently he is chairman for John Cabot University in Rome.

Riccardo Giorgio Sas Kulczycki. Born in Milan, on Feb. 17, 1950. He spent seven years at the Real Collegio Carlo Alberto, in Moncalieri, near Torino. At sixteen he left Italy for the U.S.A. to join the Choate School in Wallingford, Conn. In 1968 he entered the Wharton School (Univ. of Pennsylvania) and received a BSE in 1972. In 1974 he obtained a Master from the Grad. School of Business at the Univ. of Chicago (today Chicago Booth).

He joined the pharmaceutical company Ely Lilly, as Head of Financial Planning for Italy, Africa and the Middle East; his experience ranged also in Marketing Research. Subsequently he worked as free-lance in a Swiss consulting company for projects in Italy and the Middle East. In the eighties he organized and was a founder of the Castelgandolfo Golf Club, near Rome, designed by Robert Trent Jones Sr.

Marylyn Malkin is the current President of the Women’s Committee at Lighthouse Guild, the leading not-for-profit vision and healthcare organization, with a long-standing heritage of addressing the needs of people who are blind or visually impaired, including those with multiple disabilities or chronic medical conditions.

Paolo Martino was born in Santa Ninfa Sicily and educated in Milan before moving to New York City in 1963. Here he continued his education, studying interior design at Parsons School of Design, and marketing, business, finance, and film at NYU. In 1968, he founded Paolo M., Inc., a full service salon specializing in hair coloring. He has also developed a full line of hair and skin care products under the label “PAOLO”.

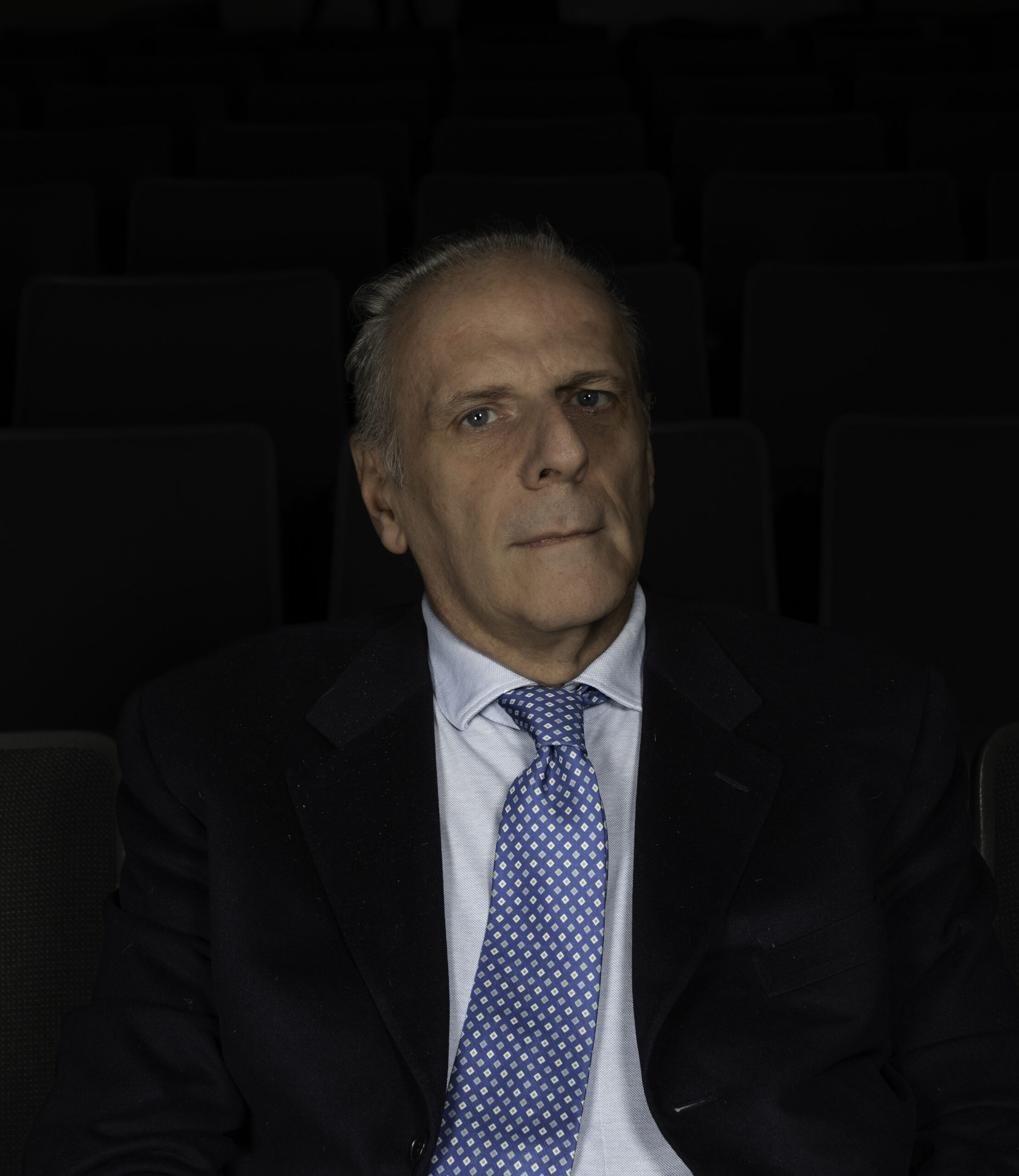

Antonio Monda was born in Velletri, Italy and currently resides in New York. He teaches in the Film and Television Department of NYU. He is the Director of the Rome Film Festival and writes for La Repubblica and has a column on the Italian edition of Vanity Fair. He has organized exhibitions for the Guggenheim, the Museum of Modern Art and Lincoln Center. Among his publications: “La Magnifica Illusione”, “The Hidden God”, “Do you Believe?” and the novel “Assoluzione”. He is the co-founder and the artistic director of the Literary Festival “Le Conversazioni”. He has directed the film “Dicembre”, presented at the Venice Film Festival.

Federica Olivares is the Founder and Director of the Master in Advanced Public and Cultural Diplomacy for International Relations of the Catholic University of Milan. She has served as Cultural Advisor to the Italian Minister of Foreign Affairs and as Coordinator for the Year of Italian Culture in the United States in 2013.

She received her degree in monetary policy from Milan State University and has studied economics in the US and international politics and economics at the Cini Foundation in Venice. She is the founder and CEO of the publishing house Edizioni Olivares.

Ennio Ranaboldo is the Head of Martin Bauer’s business in North America. Martin Bauer is a Bavarian, world leading manufacturer of botanical ingredients for the food and beverage industries. He was the New York City-based CEO of Lavazza North America, for over seventeen years. Born in Turin, Italy, in 1961 and a graduate of the local university, he’s married, a father of three children and lives in Williamsburg, Brooklyn. He is also the author of a book on J.D. Salinger, published by Mursia in 1999. Ennio joined the Casa’s Advisory Board in 2010.

Salvatore M. Salibello founded Salibello & Broder in 1978 and is the firm’s managing partner. Sal brings more than 40 years of knowledge and professional experience in public accounting to each of his engagements. Prior to founding Salibello & Broder, Sal spent 11 years with Big Four accounting firms where he specialized in providing distinct services to various types of organizations, particularly small businesses and middle market companies.

Currently, he sits on the Board of Directors of three publicly traded closed-ended mutual funds for Gabelli Asset Management and Russ Berrie and Company, Inc. where he is the chairman of the audit committee. He has obtained the status of Cavaliere from the Order of Merit of the Republic of Italy and held several positions on the Board of Directors of the National Italian American Foundation, and he is currently their Executive V.P. He received his undergraduate degree from St. Francis College and received a Master of Business Administration degree from Long Island University.

Nicola Tegoni is a Partner at Dunnington, Bartholow & Miller LLP. He is chair of Dunnington’s Immigration practice group and co-chair of Dunnington’s Italy Desk practice group.

He is a Member of the Sovereign Council of the Sovereign Military Order of Malta and Counsellor and Legal Adviser at the Permanent Observer Mission of the Sovereign Military Order of Malta to the United Nations.

Mr. Tegoni received his Bachelor of Arts degree, Magna Cum Laude, from Brandeis University and his Juris Doctor degree from Suffolk University Law School.

Guido Zerilli-Marimò, the chairman of Italy’s esteemed pharmaceutical company Lepetit, considered his greatest achievement to be shaping the lives of countless young individuals, imparting life’s wisdom and pitfalls.

He established cultural organizations, including the Associazione Italo-Americana and Centro di Azione Latina, offering courses and scholarships in various subjects and fostering educational opportunities abroad.

A tribute from a close friend reflected Guido’s impact on the world. Their competitive yet warm relationship in the pharmaceutical industry spanned the globe during a post-World War II era of rebuilding. Guido’s imaginative competence as a competitor was matched by his caring and unselfish nature as a friend.

New York held a special place in Guido’s heart, a city he saw as a universal spirit embodying the future. In 1988, his wife, Mariuccia Zerilli-Marimò, chose New York University as the home for his living memorial, Casa Italiana Zerilli-Marimò. This institution is dedicated to the study of Italian language, culture, and heritage, strengthening bonds between Italy and the United States. Guido’s vision was clear: to create a lasting source of inspiration and motivation for the benefit of humanity, a legacy now realized through Casa Italiana’s commitment to education and culture.

Baroness Mariuccia Zerilli-Marimò was born in Milan in 1926 and completed her studies in History, Languages, and Literatures at the University of Lausanne. She is the widow of Baron Guido Zerilli-Marimò and the mother of Maria Chiara Zerilli.

Baroness Zerilli-Marimò was extremely active in her philanthropic and cultural pursuits. She was a member of the Delegation of the Permanent Mission of the Holy See to the UN and sat on several prominent boards, including the Frick Collection, the Board of Trustees of New York University, La Scuola Guglielmo Marconi, and the National Italian American Foundation. She was a member of various cultural organizations throughout the world, including the Metropolitan Opera, the Friends of La Scala New York, the Metropolitan Museum of Art and Friends of La Pietra.

In 1990, she established Casa ltaliana Zerilli-Marimò at New York University, allowing for the creation of a self-standing Department of Italian Studies – now ranked one of the best in the country – where she served as Chair of the Advisory Board until she passed away in 2015.

Learn more about Baroness Zerilli-Marimò and her work via the articles below.

Following are the words of Casa Italiana Director Stefano Albertini, pronounced on the occasion of the Memorial Tribute to Baroness Mariuccia Zerilli-Marimò.

By submitting your email you confirm that you

agree with our Terms of Service.