Editor's Message

Radical Poets of Different Feathers

“I am glad and honored to have been asked to gather this provisional tribe of American and Italian radical poets, and be the town crier announcing the future Reappearance of the Pheasant.”

The poems printed below are all hitherto unpublished. Either fully unpublished as those written by the American poets, or published here for the first time in their English translation, as those penned by the Italian poets. These texts, plus many others, were supposed to be read by their authors at a gathering of American and Italian poets, scheduled to take place at the Casa Italiana Zerilli Marimò of New York University and at the Italian Cultural Institute of New York on April 8, 9, and 10. Due to the fact that COVID-19, just like the devil “rammed its ugly tail into it,” as the Italian saying goes, the event had to be postponed to November 11, 12, and 13, dates which, incidentally, mark the thirty-second anniversary of the founding of the Casa.

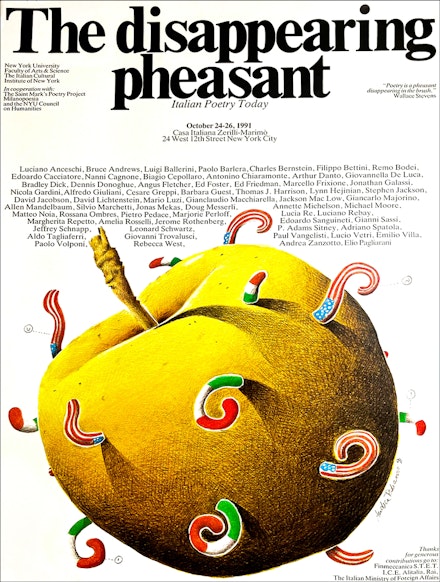

The Reappearing Pheasant, the title we chose for it, hearkens back to another encounter, or more accurately a summoning, also held at the Casa a year later in 1991. It was called The Disappearing Pheasant.

This back and forth of pheasants, and their emblematic relation to poetry must be explained and put into some perspective, provisional as it may be.

Initially, in fact, there was only one pheasant, the disappearing one, a glimpse of which could be found in the pages of Wallace Stevens’s Adagia compiled between 1934 and 1940. Many of these aphorisms address poetry or some issue related to it: “Poetry must resist the intelligence almost successfully,” or “All poetry is experimental poetry,” or indeed “Poetry is a pheasant disappearing in the brush.”

You see it and you don’t see it. Poetry behaves likewise: it roams the texts that host/hide its presence. It is a floating island, a locus incertus: not vague, not vacant, but prone to vagary, allusive and elusive, endowed with virtues that emerge from its erratic impulses.

You could also say that a poetic text is a source of renewable linguistic energy, and since language—the mysterious transformation of sound into sense and meaning—is what make us human, you could also call it a source of vital energy, our mental and emotional breath, the winter of our discontent and the summer of our rejoicing. Stevens, once again, said it best in his galvanizing definition of what poetry is and does: It “is a finicky thing of air that lives uncertainly and not for long, yet radiantly beyond much lustier blurs.”

He even tried to be theoretical about it. In the very brief introduction to his The Necessary Angel, he writes:

One function of the poet at any time is to discover by his own thought and feeling what seems to him to be poetry at that time. Ordinarily he will disclose what he finds in his own poetry by the way of poetry itself. He exercises this function most often without being conscious of it, so that the disclosures in his poetry, while they define what seems to him to be poetry, are disclosures of poetry, not disclosures of definitions of poetry.

The disappearing pheasant struck me, back then, as the effect of a promissory note that a number of Italian poets would have been happy to endorse. One of them in particular, Alfredo Giuliani, in his introduction to the 1961 anthology of the Novissimi—which caused a very fertile havoc in the panorama of postwar Italian poetry, and of which Federica Santini and I have edited an English version (New York, Agincourt Press, 2017)—had expressed similar concerns, couching them, however, in a perhaps more accessible, and historically determined, proposition:

The aim of “true contemporary poetry” remarked Leopardi in 1829, is to increase vitality; and having made this unsettling observation, he added that in times like his own, poetry was rarely capable of such a feat. … We have a linguistic concept of vitality … Undoubtedly in every age Poetry cannot be “true” unless it is “contemporary.” To the question then of what it means to be contemporary there can be only one answer: poetry is to be contemporary with our own perception of reality, or rather with the language that reality speaks within us through its irreconcilable signs. The aforesaid increase, derives then from an opening, a shock, which puts within our grasp an occurrence in which we may rediscover ourselves.

It was a wake-up call, a clean break-away from the quicksand of pre-war lyrical hermeticism in which, despite the enormity of recent events historical events, such as the twenty-one-year-long Fascist dictatorship, the Nazi occupation of the country, and a bloody resistance that all too often looked like a civil war, Italian poetry post-1945, and for the whole decade of so-called reconstruction—of buildings, not of ethos and/or language—was largely bogged down.

A singular quasi-coincidence. Charles Bernstein reminds me that: “I Novissimi was published just one year after the iconic anthology of US novel/young poetry, Don Allen’s [The] New American Poetry [and that] the radical potential of both, and some of the limitations, might well be compared.”

I should also add that, in his own terms, and though much less interested in the grammar and rhetoric of experimentalism, a term which, however, he was among the first to use, Pier Paolo Pasolini and his fellow-travelers, Francesco Leonetti and Roberto Roversi had denounced the disturbing inertia that characterized Italian poetry in the aftermath of World War II, founding in 1956 the short-lived but quite pugnacious journal, Officina (Workshop), a title whose labor-related overtones can be easily identified.

Innovative as they declared to be, and as they indeed were, both the “Novissimi” and the “Officina” poets, drew strength and from a literary tradition that class-room teaching had, if not ignored, certainly, emasculated.

Revisiting authors whose works educators—few exceptions allowed—had turned into an interminable list of predictable elegies, frustrating invectives, and rhymed examples of poorly disguised arrogance, brought to light unsuspected treasures of “poetic thinking.”

Probed anew by Giuliani, the reflections on the art of poetry disseminated in

Leopardi’s Zibaldone (heroically translated into English under the stewardship of Michael Caesar and Franco d’Intino, and heroically published a few years ago by Jonathan Galassi at Farrar, Straus and Giroux) proved to be, couched as they are in philologically somber jargon, as revolutionary as some of the French symbolists’ non-renounceable assumptions (points of no return, really) such as Rimbaud’s Lettre du Voyant or Mallarmé’s La penultième est morte or indeed Baudelaire’s rebel yell: “Hypocrite lecteur,—mon semblable,—mon frère!”

Spurred by a dramatic awareness of what language does (and can do) to and for poetry, sustained in their “archeology of morning” (the “primitive” pre-Dantean Italian poets played a major role), and ultimately determined to establish a new responsible and productive link between writer and reader, poets Alfredo Giuliani, Elio Pagliarani, Giancarlo Majorino, Paolo Volponi, Amelia Rosselli, Biagio Cepollaro, Cesare Greppi, and critics Remo Bodei, Filippo Bettini, promoter Gianni Sassi, showcased their poetic wares at the Casa and St. Mark’s Poetry Project, and engaged in fruitful, though at times controversial discussions, with a number of American fellow poets and critics who, as far as Italian poetry goes, had read beyond the usual suspects (Dante and Montale and Ungaretti, sometimes Zanzotto, and God knows why Lucio Piccolo).

American interlocutors included Marjorie Perloff, Charles Bernstein, Bruce Andrews, Douglas Messerli, Rebecca West, Paul Vangelisti, Thomas J. Harrison, Barbara Guest, Arthur Danto, Ed Foster, Annette Michelson, and many others.

The energy was great, and so was the curiosity and the enthusiasm. Yet no trace of that event is left, except for the poster designed by Gianni Sassi under whose guardianship the week-long Festival Milano-Poesia ran for ten consecutive years hosting poets, artists and musicians from literally the whole world, including, from the States, John Ashbery, Amiri Baraka, Charles Bernstein, Jerome Rothenberg, Rosemarie Waldrop, Dennis Philips, Martha Ronk, John Cage, and many members of Fluxus.

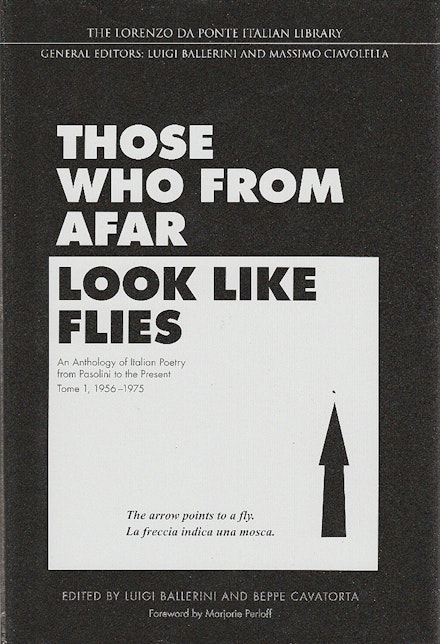

Much of the spirit of the first Pheasant, however, runs through the first volume of Those Who from afar Looks like Flies, an anthology of Italian poetry covering the years 1956–1975 that Giuseppe “Beppe” Cavatorta and I have been compiling since 2001. (We did not work at it every single day, but…) It was published in 2017 by the University of Toronto Press.

The title comes from a tale by Jorge Luis Borges in which the Argentinian writer speaks of an ancient Chinese encyclopedia, The Celestial Emporium of Benevolent Knowledge, in which the animal kingdom is divided as follows: “a) those that belong to the emperor, b) embalmed ones, c) those that are trained, d) suckling pigs, e) mermaids, f) fabulous ones, g) stray dogs, h) those that are included in this classification, i) those that tremble as if they were mad, j) innumerable ones, k) those drawn with a very fine camel’s-hair brush, l) others, m) those that have just broken a flower vase, n) those that at a distance look like flies.”

Clearly, the analogy between contemporary Italian poets adrift the in the Anglo-Saxon literary world and the winged insects is not motivated by the discomfort their ubiquitous presence may procure, but rather by the difficulty to focus on the actual profile of animals that indeed are not flies: they simply look like flies … from afar. Hopefully, ophthalmologists who specialize in contemporary poetry will certify the Flies as a valuable reading aid that may reduce the “blurriness” of the vision. Included in the two-thousand-and-some pages of Flies 1 are not just poetic texts, but critical essays and statements on poetics. The overall idea is to provide an organic profile of the main currents of poetic activity at a time when the poets who were interested in the exploration of language deployed at its poetic level by far outnumbered those who lamented its expressivistic shortcomings.

In this respect, an extremely fertile bond has existed since the war between Italian and American poetry, at least in the area which we have labeled “research poetry,” and for which Charles Bernstein, in his foreword to the second volume of the Flies (due from U of Toronto Press in 2023), has suggested the sensibly modified moniker of “searching poetry.” One example may suffice: the presence and the teachings of Ezra Pound who had been the harbinger and tenacious advocate of early Italian poetry throughout the world, and who (along with Eliot and Olson) has influenced, in purpose if not in style, poets such as Elio Pagliarani and a number of younger Italian practitioners who have in many ways transmogrified the fragmented vein of his epic narrative. Even Pasolini, after years of dissension for ideological reasons, satisfied his desire to make peace with the American poet in an unforgettable televised interview. In it, Pasolini cites the well-known lines with which Pound addresses Walt Whitman:

I make truce with you, Walt Whitman—

I have detested you long enough.

I come to you as a grown child

Who has had a pig-headed father;

I am old enough now to make friends.

It was you that broke the new wood,

Now is a time for carving.

We have one sap and one root—

Let there be commerce between us.

All you have to do is to replace Pound with Pasolini and Whitman with Pound.

With Flies 1 & 2, we have been trying to delineate for an American audience—but it may be helpful to many Italians as well—an orientation map, fully aware that the neatness of the picture reflecting tendencies, conflicts, ideologies, and styles at work in the writing of Italian poetry from the late ’50s to the early ’70s, could not be replicated for the following decades, characterized as they are by a rethinking and a re-elaboration of the preceding avant-garde impulses and by an incredibly complex overlapping of political motives, not to speak of the day by day experience of life traversed by a sense of uncertainty never experienced before.

Intending to build a credible bridge connecting American and Italian contemporary poetry scenes, and traveling, so to say, in the opposite direction, we have been also fully immersed in a project to make available to an Italian audience specimens of the post-Beat generation American verse. This adventure is imprinted with a different line of thinking. We called it Nuova Poesia Americana (not a particularly provocative title, as you can plainly see) and divided it in six separate zones, each condensed in a bilingual volume, and chosen on the basis of a recognizable—or at least plausible—genius loci, an idea whose roots are planted, though, at times, subverted, in the legacy of Gertude Stein’s Geographical History of America: or the relation of human nature to the human mind.

In cooperation first with Paul Vangelisti, and subsequently with Gianluca Rizzo, five tentative poetic zones plus one have been tentatively identified: Los Angeles and the Far West, San Francisco and the Bay Area (plus the north western states), Chicago and the prairie towns, New York and the tri-state area, Washington (maybe), and Kansas City, a city that, possibly unbeknownst to its inhabitants, postwar Italians have imagined being (albeit, at time, with a touch of humor) the quintessential emblem of America, and as such, particularly suited to house the voices of those poets who did not fit in the previous categories.

Let’s see if we can throw some light on this would-be criterion by means of an example, actually two: the poets included in Chicago and the Prairie Towns (Torino: Aragno Editore, 2019) seemed to come alive viewing their poetry through the historically connotated lens of what we have come to know as the “culture of the frontier.” This meant revisiting, on the one hand, such classic essays as Frederick Jackson Turner’s “The Significance of the Frontier in American History,” or Henry Nash Smith’s “Virgin Land,” and, on the other, suggesting meaningful links, and all lexical and metric considerations aside, between much of the poetry written today in that incredibly complex fluvial system connecting the Great Lakes with the Gulf of Mexico—which, furthermore, was no secondary theater of conflict during the civil war—to such monuments of the past as Carl Sandburg, Vachel Lindsay and, of course, Edgar Lee Masters, whose poetics went hand in hand with a sense of social commitment and responsibility.

In the case of Los Angeles and the Far West, a volume that is in the making right now and will also be published by Aragno in 2023, the concept of the frontier undergoes a substantial metamorphosis. First it comes to an end and lends itself to be seen as some sort of earthly paradise (notwithstanding earthquakes and devastating wildfires). Then, since it cannot any longer move forward, for lack of land, it verticalizes itself: it becomes “moving pictures” and spreads throughout the world images of America’s recent past, the conquering of its ultimate frontier, as it were, the Far West, with a retinue of cowboys and Indians, and blue coats, and Gene Autrey and John Wayne, whose equestrian monument sits sadly along Wilshire Boulevard in Los Angeles, not very far from the headquarters of Larry Flynt’s girly magazine Hustler.

Justifying such procedures is not easy. Sometimes the shoe fits like a glove, sometimes it hurts a little. But we live in an age of aporias, and comfortable partitions, desirable as they may be, do not translate into illuminations. Exceptions and contradictions, instead, may do the trick. Our categories are no categories at all. They are suggestions to be handled with care and with a grain of salt. They seem to be more effective as instances of magic thinking than as rational, linear, sequential, metalinguistic constructs. At any rate they are an invitation to climb a ladder which, after reaching the last peg of it, you are supposed to discard, as Wittgenstein suggested, even though you may not have leaned it, previously, against the slope you wanted to climb, as Sextus Empiricus had advised many centuries ago.

In the thirty-two years that separate the disappearing from the reappearing pheasant, much has changed. To begin with, almost all the poets who came over from Italy are no longer with us. In the fall, we shall try to bring some of them back, by means of virtual narratives. Many younger poets have found their legacy “hard to swallow” and have retraced their steps to more accessible and content-minded verbal and verbo-visual compositions. The narrative of personal experiences has frequently ignored, or brushed aside, or even treated with contempt the linguistic obsession of earlier days, though in the end, its resilience has been identified as a necessary condition of poetry writing, and in the best cases what the poem is about and what the poem is made of have combined in the necessary dance of the intellect that no consequential, exploitative, capitalistic, “either/or” logic can vilify and, worse still, annihilate. A demand for more recognizable referents, a legitimate thirst for a less intimidating legibility, should never become an opportunity to desert the necessity of learning how to read a poem, a text in which punctuation (or lack thereof), proleptic occurrences, rhyme patterns, rhythm, and all kinds of rhetorical and grammatical functions must be communally accounted for, and agreed upon, before individual appropriation of meaning (a truth that may not be demonstrable, but is always undeniable) can occur.

It has been a while since we have deserted the idea of separating the rational from the irrational and yet emotions which are nothing but the springboard for the writing of a poem have been deployed, all too often, as the objects themselves to be captured and rendered alive. This implies a request made on the reader to share in the feeling proposed by the author; but the request goes unheeded unless the private utterance can be shown to have universal or at least community-related value.

The readers of the Rail and those who listen to the daily encounters impeccably produced by Nick Bennett are familiar with the re-invigorating effects hidden in the hour of Radical Poetry, of which of course there are dozens of varieties. Let me just add here that while we should not be oblivious to its political implications, the epithet “radical” comes from the Latin “radix,” that is to say “root.” Now the function of roots is to absorb nutrients from the soil. The richer the soil the happier the root, the happier the roots the stronger the plant. And so lets poetry absorb energy from language, just as lilacs, T.S. Eliot reminds us, are bred out of the dead land during the month of April which may be the cruelest month, and yet is capable of stirring dull roots with spring rain and mixing memories and desires.

I am glad and honored to have been asked to gather this provisional tribe of American and Italian radical poets, and be the town crier announcing the future “Reappearance of the Pheasant.” To them and to the readers of the Brooklyn Rail I’d like to dedicate, as a quick adieu, which is also an invitation to keep in touch, the following lines of mine, in which, none other than Dante Alighieri is called upon to give credence and support to one of Pound’s more felicitous ideas.

Homage to Ezra Pound

I wholly agree with Pound who wrote that when

a nation states that road roads cannot be built

for lack of funds, it is the same as saying they

can’t be built for lack of miles. I pay no heed

to fools who credit rumor rather than the truth.

They’re better known in wintry times, the ashen

screams of those who find no peace, count every

step, ride the road to Damascus, persecuted

by the spread-out wings of a redemptive plan.

Does increase resonate with fasting, is lethargy

an urge to wager, is it like crimes committed

in cold blood, or, faute de mieux, the fraudulent

equation of income and finance? I am even more

with him when, just like rain mixed with perfect

snow, he counsels souls benumbed by one

unspoiled death drive to seek the burden of

a freeze-frame, an impervious surplus-value

so slow in coming, held at gun point by Minos

who judges and assigns as his tail twines